Agile Octopus Histograms

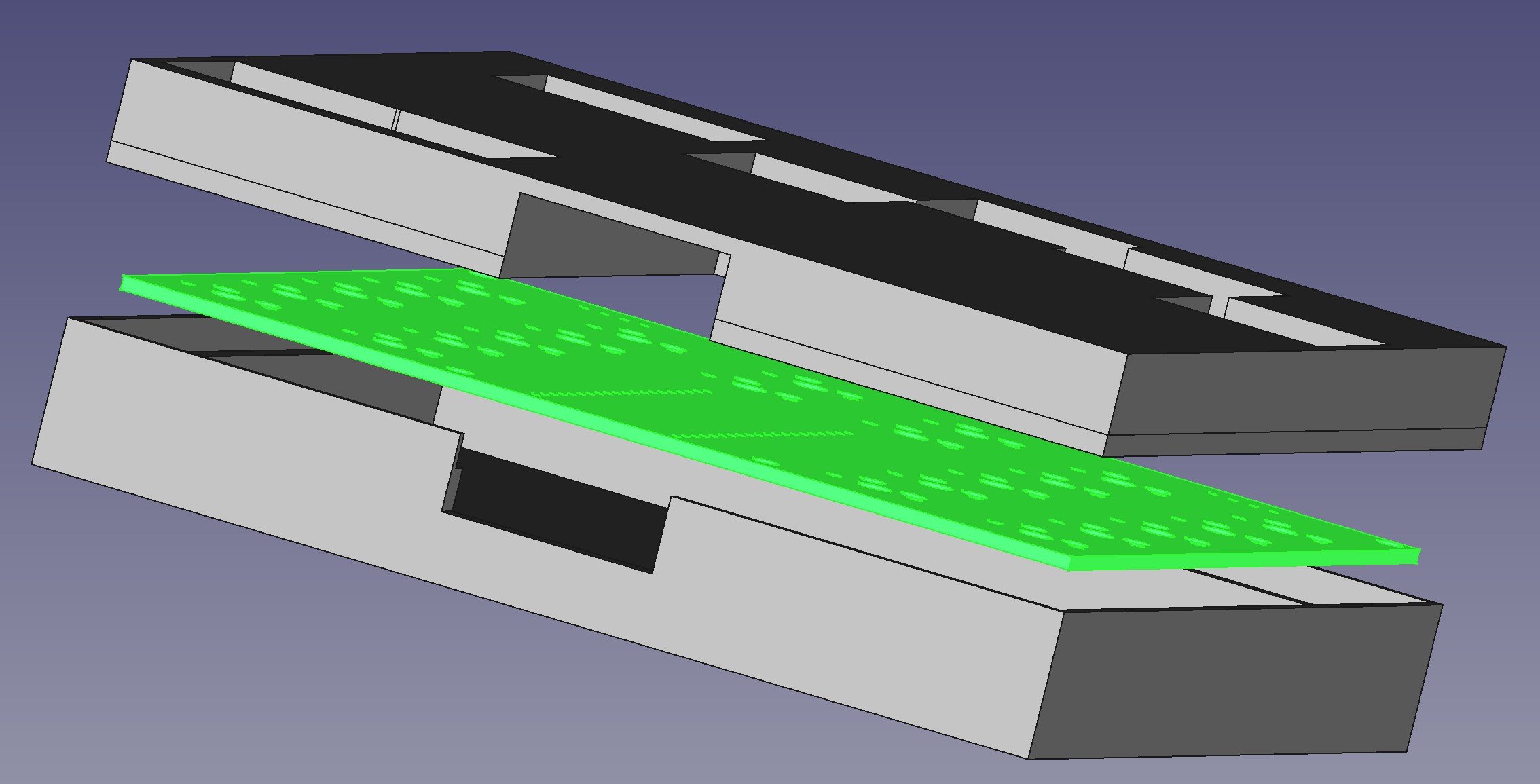

/This is a very nice lcd panel

I spent some time today working on my Agile Octopus price display. Agile Octopus is an electricity tariff where you get a different price every half-hour during the day. A while back I made a device that would get the current price and display it, but now I’ve added a little histogram that displays upcoming prices for the rest of the day. The picture above was taken at 7:14 pm. The solid lines in the histogram are the hours and the dotted lines the half hour prices. On the right you can see the minimum and maximum prices. It looks like the prices will be going down over the evening. We’ve found this quite useful when deciding when to put the washing on or bake a cake. The display is powered by a Raspberry Pi PICO-W driving a rather nice LCD panel from Pimoroni.

It’s actually rather pleasing to make something that folks actually find useful and might even save us money.