Infinitely Baffled

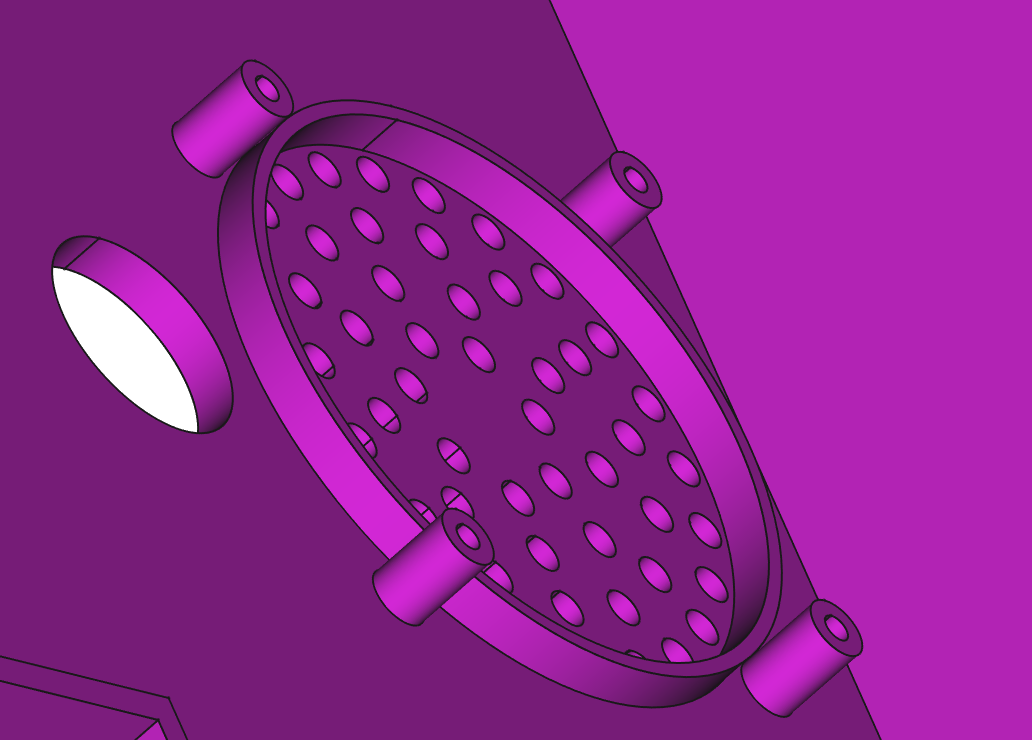

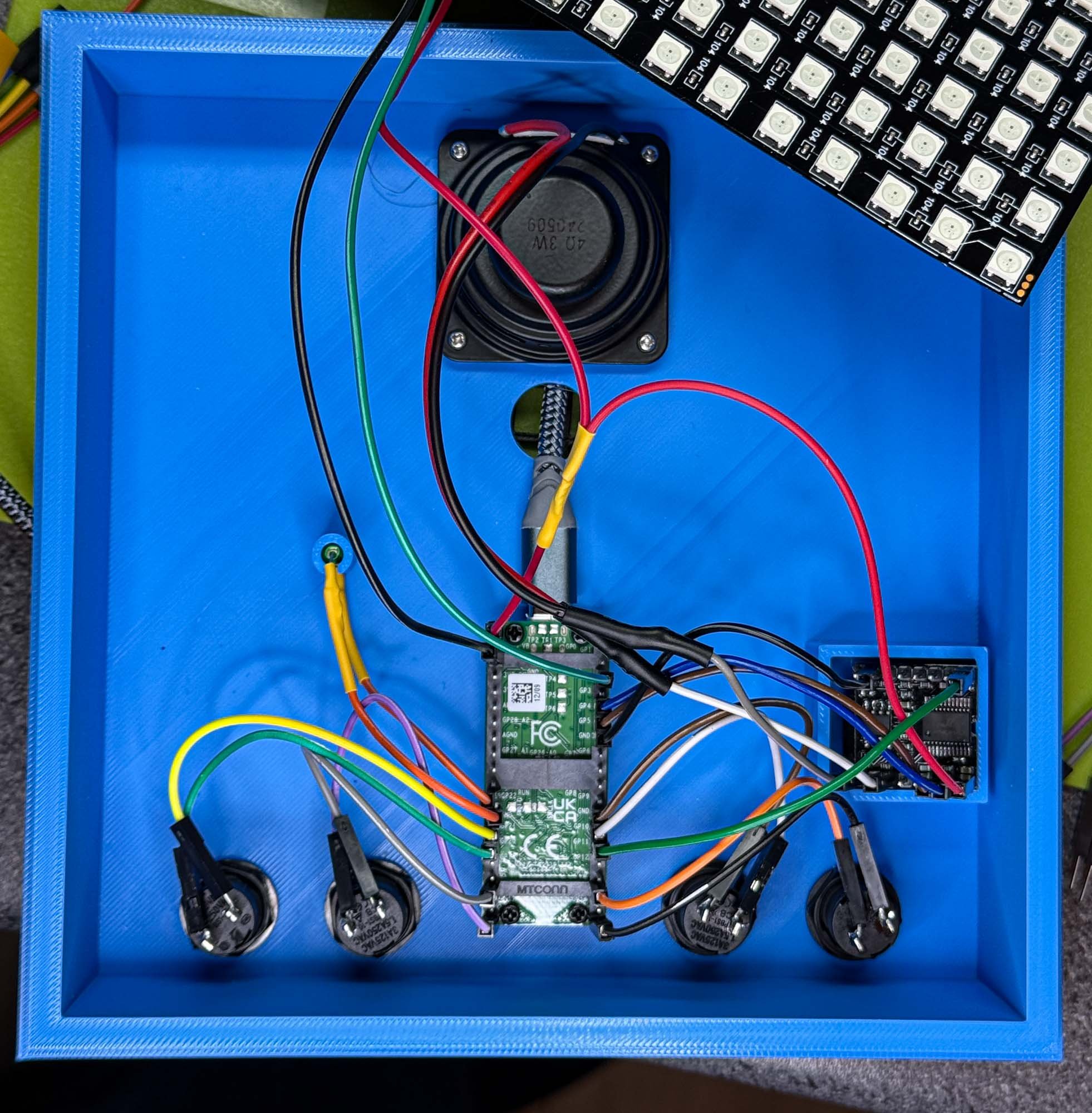

/The box above took over three hours to print. It’s perfect in every way except one. I’m going to have to print it again. The problem is with the speaker fitting at the bottom of the box. The speaker fits into the circle and is supported by four pillars. But the pillars are too high.

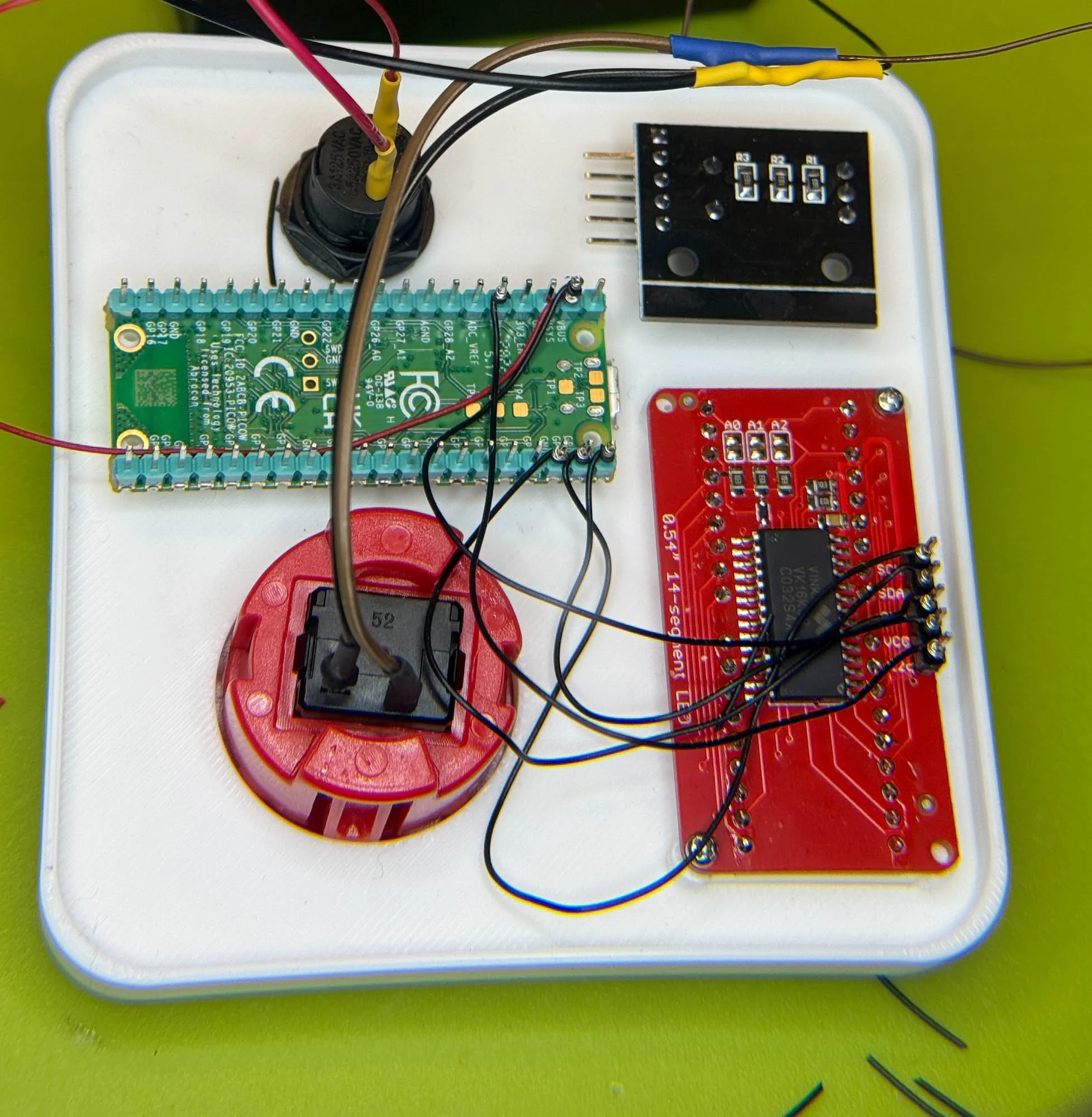

You can see the problem here. If I put the speaker on top of the pillars there will be a gap between the speaker and the hole it fits in. This makes it sound awful. To understand why we have to learn about about how speakers work.

The cone in a speaker goes backwards and forwards, pushing the air in front of the speaker to make sound waves we can hear. We really don’t want to hear anything from the back of the speaker because, although it is also sound, it is going the “wrong way”. The sound term for this is “out of phase”. When air in front of the speaker is being pushed forwards, air at the back is being pulled. If sounds from the front and the back meet up they can interact in ways that don’t sound nice.

Some speakers use carefully designed boxes which take the out of phase sound from the back of the speaker and reflect it in some way to invert the phase so that it adds to the sound. Other speakers solve the problem by putting the speaker in a sealed box from which the sound from the rear of the speaker can’t escape. These are called “infinite baffle” speakers. If you call the thing that we put the speaker into a “baffle” (which sound people do) you can see that an infinitely large baffle would stop any sound from the back of the speaker getting to the listener.

I’m trying to make my device use the infinite baffle principle. That’s why I have the circle that the speaker fits into and seals against. However, if I have a gap between the front of the speaker and the baffle I get sound leakage from inside the box and the speaker sounds rubbish.

So that’s why I reduced the height of the pillars and printed the box again. It makes a surprising difference to the sound. As to why I got this wrong in the first place: I made all the pillars in the box the same height, then I increased the height of the pillars that support the PICO In the middle of the board and that made the speaker pillars higher too.

Update: It’s just occurred to me that I have a hole in the back in the form of the power cable entry. I might convert that into a socket (or add a seal) and see if that makes it sound even better.